“No, we do not need this kind of music. It only serves the revisionists and the bourgeoisie as a narcotic to sedate the masses, especially the youth.”

Enver Hoxha’s address to the IVth Plenum of the Central Committee of the Party of Labour of Albania, held in Tirana on June 26 – 27, 1973

Click on image to view full document.

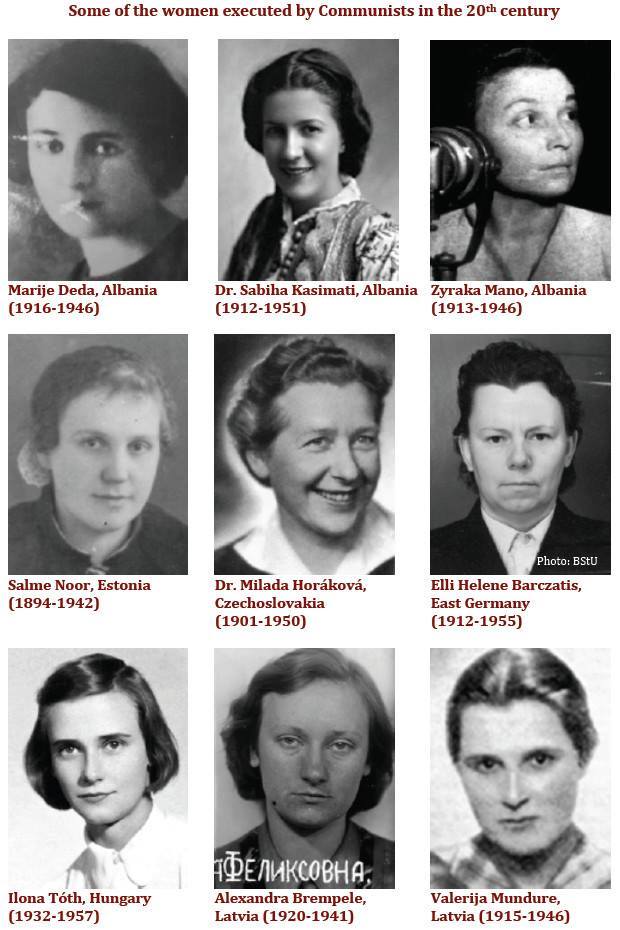

The images above show an idealized social realist painting of Enver Hoxha with a group of young women, and an image from a document published on memoryandconscience.eu in 2017. The latter was published alongside a call for a minute of silence for the millions of women who fell victim to the Communist dictatorship in Europe. The contrast of these two images reflects the extremes of narratives about women under Hoxha’s regime. While the emancipated woman was central to the image of the new society that Hoxha and his regime wanted to project, an analysis of Hoxha’s own rhetoric reveals how his regime protected, strengthened and even redesigned patriarchal Albanian traditions, while trivializing issues at the heart of gender inequality, including violence against women.

As Hoxha reimagined his new Albania, both ancient national customs and foreign “anti-socialist” influences were presented as enemies to his vision; he expressed these threats in two ostensibly negative ideas of conservatism and liberalism. While these terms were fluid and tailored to serve each stage of Communist power conservatism generally referred to traditional patriarchal values, which stood in the way of progress. Liberalism on the other hand was used to define any value held by capitalist or revisionist enemies that were a potential danger to the new socialist Albanian society. Conservatism related to women’s emancipation, as an expression of traditional elements that undermined it, as they were still confined within the strict gender roles in the family structure. Hoxha’s Women’s Emancipation campaign focused on women’s education and her participation in the work force.

Hoxha’s 1972 speech “About Strengthening Socialist Democracy in the Family.”[2] (Hoxha: vol. 49, 46) criticized conservatism and addressed inequality for women within the family. His emancipation plan was to provide equal education and participation in the work force, but the responsibility for changing their condition both within the family and in the workforce fell entirely on women themselves.

When the head of a woman’s group in the region of Permet complains to Hoxha that her organization’s initiatives are ignored by male colleagues, Hoxha responds, “What do you think comrade Liri, do you find it appropriate that in Party, professional, and youth meetings both men and women participate, whereas in the meetings of your (women’s) organization, especially in the leadership there are only women?…I think to be heard by these people, sometimes you should invite men into the women’s council.”[4] Similarly it is the wife’s responsibility to demand that the husband help her with the household chores that evidently remain her primary responsibility, and it is the mother’s responsibility to teach her son to help her. In several cases Enver Hoxha even suggested that women’s ignorance was responsible for the inequality in the home. (Hoxha: vol. 49, 52)

One of the most significant moments in the historical speech of 1972 came when the communist leader referenced domestic violence. As Hoxha explains that women (just like men) desire freedom and knowledge even when “[s]ometimes over them weigh insults, and even beatings by their husbands.”[5] He does not pause and address domestic violence as a separate issue, nor does he at any point in his speech chastise men for it. For Hoxha, a man’s responsibility in achieving socialist democracy in the home is limited to housework help, or bringing the word of the Party to their still uneducated wives.

Even in his most direct address against conservative values in support of women’s emancipation, Hoxha never truly challenged patriarchal values, instead he enforced them. That liberalism was far more dangerous than conservatism was always implicit in Hoxha’s speeches. The word liberalism applied to foreign capitalists and revisionists, who he claimed were becoming increasingly hostile. But it was not until the political purges that swept the cultural leadership of the country in 1973, that the debate of conservatismvs liberalism took center stage.

[2] Për Thellimin e Demokracisë Socialiste në Familje

[3] By 1972, the Albanian communist party had become the Albanian Labor Party.

[4] Original: “Si thua ti, shoqja Liri, a e gjeni te rregullt qe ne mbledhjet e organizatave te parties, te bashkimeve profesionale, te rinise e te Frontit bejne pjese edhe burra edhe gra, kurse ne mbledhjet e organizates suaj, sidomos ne ato te organeve te saj drejtuese, ka vetem gra? …Une mendoj se qe t’jua vene mire veshine keta njerez, here-here mund edhe te ftohen ne keshillin e gruas edhe burra…”

[5] Original: “Nganjehere mbi to rendon sharja, bile edhe rrahja e bshkeshorteve”